What are viruses?

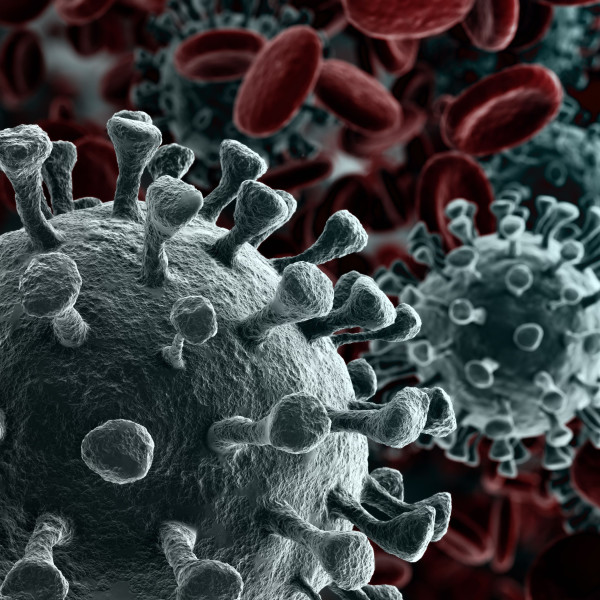

Viruses are infectious agents that can cause diseases of varying severity. They spread through aerosols, droplets, during sex, through contaminated food or through smear infection. Since viruses are only between 20 and 300 nanometres in size, they cannot be detected under an ordinary light microscope. An electron microscope is absolutely necessary for identification. Unlike bacteria, viruses are not living organisms. Viruses neither consist of their own cell, nor do they have their own energy production or carry out protein synthesis. Rather, viruses are dependent on so-called host cells. These are living cells of animals, plants or humans into which the viruses penetrate. If they do not find a host cell, they die sooner or later. Similar to bacteria, viruses can also take on many different forms. Sometimes they can have a long tail like tadpoles or take on a round or rod-shaped appearance.

How are viruses built?

Viruses are quite simple. They have one or more molecules. In addition, some viruses have a protein coat:

- Genome: contains the genetic material of the virus. Depending on its sugar building blocks, this can be built as deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or ribonucleic acid (RNA). Doctors therefore distinguish DNA viruses such as adenoviruses, herpes or smallpox viruses from RNA viruses, which include HI viruses, corona, flu, hepatitis or measles viruses.

- Capsid: This is what the protein coat around the virus genome is called. Taken together, they are called nucleocapsid.

- Envelope: Some types of viruses still have an outer envelope, which consists of a lipid bilayer. They can consist of special receptor proteins called spikes, which help the virus to attach to a host cell.

The so-called viroids are probably among those that are the simplest in construction. They only have a genome, i.e. a ring-shaped RNA molecule.

Do all viruses cause diseases?

Many viruses occur in our natural environment. However, not all viruses automatically infect humans or necessarily cause diseases. Often, the human immune system prevents viruses from entering the body at all. Nevertheless, there are serious infections that are triggered by viruses. In addition to the common cold, these include cold sores, gastrointestinal infections and HIV/AIDS. The typical childhood diseases measles, rubella and chickenpox are also triggered by viruses.

How does a virus spread?

Viruses need host cells to multiply, which can be red or white blood cells, for example, but also liver or muscle cells. To do this, they enter our body and begin to multiply inside the human cells. To do this, the virus attaches itself to the host cell and lets it produce the respective building blocks that are needed for reproduction. This is because once the genetic material of the virus is released, the host cell is forced to reproduce virus particles and thus help the virus to spread. After the host cell has completed its task, it dies and releases the viruses, which in turn seek out new host cells. The life cycle of viruses is structured as follows:

- Docking (adsorption) to a host cell: The virus binds to the surface proteins in the cell membrane.

- Penetration into the host cell: This is achieved by fusion or endocytosis.

- Release of the viral genome (uncoating) inside the host cell: The viral nucleic acid is released from the protein coat and the viral envelope, if present.

- Multiplication (replication) of the required viral building blocks: The genetic material of the virus is replicated and read.

- Assembly of new viruses: The virus is packaged in a protein coat.

- Release of the new viruses after the host cell has died: In some enveloped virus species, this is done by bursting of the host cell.

How quickly do vires spread?

Doctors call the period of time from the beginning of the uncoating phase until the first new viruses appear in the host cell an eclipse. This phase lasts differently depending on the type of virus. While it can be about 30 hours for adenoviruses, this phase can be eight to ten hours for retroviruses and about five hours for herpes viruses.

How are virus-related diseases treated?

The type of viral treatment depends entirely on the particular virus, its severity and the course of infection. Unlike bacteria, viruses cannot simply be treated with medication. In particular, the use of antibiotics is ineffective for viral diseases. If a doctor nevertheless prescribes antibiotics, this is usually because a bacterial infection can also develop as a result of the viral infection. This is to be treated or prevented by antibiotics. In addition to prescribing antibiotics, however, it is also possible to prescribe antiviral drugs, so-called antivirals. However, these are only effective against individual types of virus. In some cases, antivirals can suppress the spread, i.e. the reproduction of viruses, but not kill them.

In addition to antivirals, there are also so-called interferons. These are the body's own messenger substances. They are produced by many body cells in response to a viral infection. Since they have an antiviral effect, they play an important role in the body's immune defence. In order to be able to treat patients with a weakened immune system in particular, artificially produced interferon preparations are now also available. These can be used as medicines against certain viruses, for example chronic courses of hepatitis B and C and/or against genital warts.

Virus variants

To ensure their survival, viruses act very flexibly. For example, the flu virus (influenza virus) is constantly changing in order to penetrate the human organism more easily past the body's own defences. The so-called flu vaccine therefore only protects for one year, as the influenza virus has already changed again with the next wave of influenza. Therefore, the vaccine has to be adapted to the characteristics of the new virus mutants every year.

How do viruses differ from bacteria?

Both viruses and bacteria are infectious pathogens. However, they differ from each other in the following ways:

- Nucleic acid: While the genome of bacteria always consists of DNA, that of viruses can consist of RNA or, more rarely, DNA.

- Cell plasma (cytoplasm): While bacteria, similar to human and animal cells, consist of a cell with cytoplasm inside, viruses have nothing comparable.

- Reproduction: While almost all bacteria have their own metabolism and independent cell reproduction, viruses depend on host cells to spread.