What is anal carcinoma?

An anal carcinoma is a malignant tumour of the anal canal. This is the outer end of the large intestine, which extends from the skin of the anal verge to the rectum. The so-called basaloid carcinomas are often found above the inner border of the anal canal. The so-called squamous cell carcinomas can develop in the anal canal itself and the anal margin tumours, which often also occur as squamous cell carcinomas or much less frequently as adenocarcinomas. The anal margin tumours are localised to the border of the outer skin. Approximately two thirds of all anal carcinomas are squamous cell carcinomas.

Compared to colon cancer, for example, anal carcinoma is relatively rare. Men are more often affected by anal carcinoma than women. Whereas women are more likely than men to develop carcinoma of the anal canal. Certain sexually transmitted diseases and chronic infections can favour the development of anal carcinoma. Often, anal carcinoma can be noticed by blood deposits in the stool, pain during bowel movements and/or itching in the anal area. However, these rather unspecific symptoms can also indicate haemorrhoids.

What risk factors contribute to the development of anal carcinoma?

There are various risk factors that can be blamed for the development of anal carcinoma. These include:

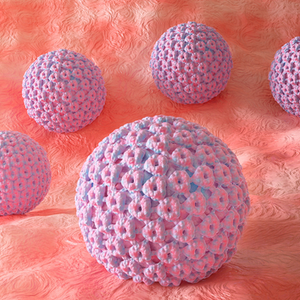

- an infection with human papilloma viruses: contribute to the development of anal carcinoma in 80 to 85 per cent of all cases.

- DNA viruses: Types HPV 16, 18, 31 and 33 ("high risk") are associated with cancers of the anus, cervix and vulva, which is why they carry a particularly high risk of also developing anal carcinoma. They are sexually transmitted.

- DNA viruses "low-risk": are responsible for the formation of benign skin growths, for example warts in the genital area. However, they can also be responsible for the development of squamous cell carcinomas via intermediate stages.

- weakened immune system: accelerates the development of cancer, as tumours can only be fended off to a limited extent; HIV patients or transplant recipients in particular therefore have an increased risk of developing anal carcinoma.

- unprotected anal intercourse

- Smoking

How can the development of anal carcinoma be prevented?

Since the development of anal carcinoma is very likely to be linked to human papilloma viruses, you can protect yourself from them by using condoms. In addition, an infection with cancer-causing HPV viruses can be prevented by vaccinations. If you notice blood in your stool, itching and/or burning in the anal area, these can be the first signs of anal carcinoma, which should be clarified immediately. As with other cancers, the earlier an anal carcinoma is diagnosed, the better its chances of being cured. In Germany, patients are therefore offered a digital examination of the anus and a test for hidden blood in the stool (occult blood in the stool) as part of an early detection examination.

What symptoms can indicate anal carcinoma?

An anal carcinoma can be noticed by rather unspecific symptoms. Especially in the early stages, the following symptoms may occur:

- Blood deposits on the stool

- Constipation; stool irregularities

- Difficulty controlling bowel movements

- Pain during bowel movements

- stools with a strange shape, such as indentations

- Itching in the anal area

- Foreign body sensation

- enlarged inguinal lymph nodes

- general fatigue, unwanted weight loss, night sweats

An anal carcinoma can be accompanied by other chronic infections of the anal area, such as haemorrhoids, fissures, fistulas, herpes, condyloma and/or psoriasis. These diseases should definitely be clarified by a doctor.

How is anal carcinoma diagnosed?

During a proctological examination, the typical initial symptoms of an anal carcinoma should be thoroughly clarified. First, the doctor will palpate the anus and the lymph nodes in the groin for possible swelling. Then the function of the sphincter muscle and the neighbouring structures will be examined. If there are any abnormalities, the doctor will perform a rectoscopy to take a tissue sample (biopsy).

After the biopsy has confirmed the diagnosis of anal carcinoma, the stage of the cancer (staging) must be determined. A complete colonoscopy can exclude secondary tumours, polyps or inflammations. A sonography of the abdomen can also exclude or confirm the formation of metastases in the liver and provides information about whether there is a urinary blockage in the kidneys. In addition to these two examination procedures, a chest X-ray is taken to assess the condition of the lungs and heart. The individual stages of cancer that can be shown after these examinations are differentiated as follows:

- T1: There is a primary tumour with an extension of no more than 2 cm.

- T2: A primary tumour is present that has assumed an extension of 2 to a maximum of 5 cm.

- T3: There is a primary tumour with an extension of more than 5 cm.

- T4: The tumour has already metastasised to neighbouring organs, such as the vagina, urethra or urinary bladder. There is no infiltration of the sphincter ani.

- N0: There are no regional lymph node metastases.

- N1: The tumour has metastasised to the perirectal lymph nodes.

- N2: The tumour has metastasised to the pelvic lymph nodes and/or unilaterally to the inguinal lymph nodes.

- N3: The tumour has metastasised perirectally and inguinally (groin) and/or has even spread bilaterally into the pelvic lymph nodes and/or bilaterally into the inguinal lymph nodes.

How is anal carcinoma treated?

Anal marginal carcinoma is surgically removed after it has been ruled out that the tumour has already spread to neighbouring structures. If, on the other hand, the anal cancer has already metastasised, a combined radiochemotherapy is carried out. Radiochemotherapy has the advantage that in more than 70 percent of all cases, the patient does not have to have an artificial anus placed during the operation. If there are still remnants of the tumour after radiochemotherapy, the rectum must be completely removed and an artificial anus must be created.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal is treated with radiochemotherapy as standard. If the tumour forms again, radical surgical procedures (rectal ablation) are usually used. If, on the other hand, the anal carcinoma has already spread to the lymph nodes or to the pelvic area, radiochemotherapy is also part of the standard treatment in this case. If, on the other hand, the tumour is no longer treatable, so-called palliative measures are used to relieve the patient's pain, for example.

What is the prognosis for anal carcinoma?

As a rule, the chances of curing an anal verge tumour are better than those of a typical anal carcinoma. If an anal margin carcinoma can be completely removed by surgery, the patient is completely cured in over 90 percent of all cases. Generally, the 5-year survival rate of an anal carcinoma is between 70 and 90 percent.