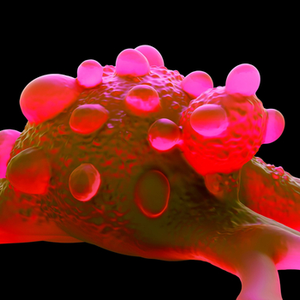

Bladder cancer at a glance

Bladder cancer (bladder carcinoma) refers to a malignant cancer that usually starts in the lining of the bladder (urothelium). On average, more men than women develop bladder cancer, with one in five under the age of 65. In the early stages, bladder cancer hardly causes any symptoms, which is why it is often diagnosed late. Doctors are still unclear about the development of bladder cancer, but they have been able to identify smoking and age as risk factors. Frequent contact with certain chemicals can also promote the development of bladder cancer.

What risk factors can lead to bladder cancer?

Risk factors that can lead to bladder cancer are mostly due to external influences such as:

- Smoking (which is responsible for about 70 per cent of all bladder carcinomas, according to medical experts): Pollutants produced by smoking enter the blood and are washed into the bladder with the urine

- chemical substances: these include above all aromatic amines, which are classified as carcinogenic and are used in the chemical industry as well as in the rubber, leather or textile industry and in the painting trade. If a worker has had a lot of contact with these substances and develops bladder carcinoma, the disease is classified as an occupational disease. The time between exposure to the chemical substances and the development of bladder carcinoma can be up to 40 years (latency period)

- chronic bladder infections: are considered a presumed risk factor for bladder cancer

- Abuse of painkillers: people who have taken high doses of phenacetin are particularly at risk

- infectious diseases of many years' standing: particularly risky is the infection of couples' flukes (schistosomes), which is particularly widespread in the tropics and subtropics and causes the disease schistosomiasis, which also affects the urinary bladder and urethra (urogenital schistosomiasis).

- Drugs used in chemotherapy: here, for example, cylophosphamide-based cytostatics play a major role and are administered for leukaemia, breast and ovarian cancer.

What are the symptoms of bladder cancer?

Bladder cancer usually manifests itself with the following non-specific symptoms:

- a reddish to brown discolouration of the urine, caused by blood in the urine, which does not have to be permanent (occurs in 80 per cent of all cases of bladder carcinoma, but can also be a symptom of urinary tract or kidney disease),

- Discomfort during urination, for example, an increased urge to urinate with the emptying of only small amounts of urine (pollakiuria) associated with or without pain (may indicate bladder cancer, although many confuse it with cystitis),

- Pain in the flanks, which often occurs in a more advanced stage of bladder cancer,

- chronic bladder infections (especially if treatment with antibiotics is unsuccessful, this can be a sign of bladder cancer)

How is bladder cancer diagnosed?

Because bladder cancer initially causes little to no symptoms and the symptoms are very non-specific, the cancer is usually only detected at a late stage. If bladder cancer is suspected, the urologist will first ask about the patient's medical history and request information about whether the urine is discoloured, whether there are problems with urination, or whether there is occupational contact with chemical substances. If blood can be detected in a urine examination, the suspicion of bladder carcinoma becomes stronger and an X-ray examination of the entire urinary tract (urography) is carried out. If necessary, an ultrasound of the abdomen (sonography) may also be ordered to determine the condition of the kidneys, renal pelvis, bladder and ureter. During a physical examination, only large bladder carcinomas can be palpated through the vagina, rectum or abdominal wall.

To confirm the diagnosis of bladder cancer, a cystoscopy can be performed, during which the patient is given a local or general anaesthetic. A cystoscopy provides information about how deep the tumour has already penetrated into the mucous membrane of the bladder. A sample of the suspicious tissue (biopsy), which is taken by means of an electric loop (transurethral electrosection of the bladder, TUR-B), is examined by a pathologist under the microscope. If the diagnosis of bladder cancer is confirmed, further examinations may follow to determine what stage the cancer is in. In addition to an ultrasound of the liver, X-rays of the chest, a computer tomography (CT) or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen can be done.

How is bladder cancer treated?

The treatment of bladder cancer always depends on the stage of the cancer, the size of the tumour, the location of the bladder tumour and how fast the tumour is growing. One treatment option is endoscopic surgery (TUR). Since about 70 per cent of those affected only have a superficial tumour that can be localised to the bladder mucosa and has not yet reached the bladder muscles, this can be removed by an electric snare. Many patients receive local chemotherapy (instillation therapy, intravesical chemotherapy) directly after this procedure to prevent the development of a new bladder carcinoma. In this case, the preventive drugs are flushed directly into the bladder after the operation. If, on the other hand, there is an increased risk of recurrence, the tuberculosis vaccine BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guérin) can also be administered directly into the bladder.

If the bladder carcinoma is already deeply ingrown, in some cases the bladder must be partially or completely removed (cystectomy). In addition, the surrounding lymph nodes and the urethra are also removed if the latter is already affected by the tumour. In men, the prostate and the seminal vesicle can also be removed, while in women at an advanced stage, the uterus, part of the vaginal wall and the ovaries can also be removed.