What is eye cancer?

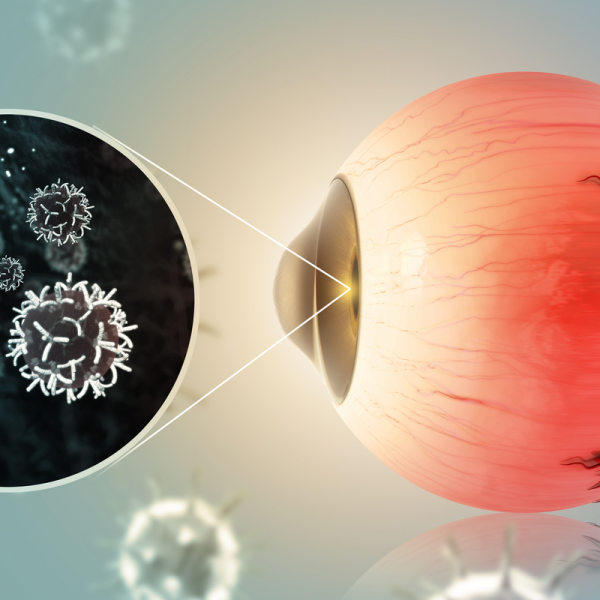

Eye cancer is a rather rare cancer that can appear in all areas of the eye.

Babies and small children can also develop eye cancer, with retinoblastoma being the most common type of tumour in this age group.

In adults, on the other hand, a so-called choroidal melanoma often develops.

While some eye cancers have hereditary causes, others develop due to external influences such as excessive sunlight.

Eye cancer should be treated at an early stage, which often proves difficult because the cancer is asymptomatic for a long time and therefore remains undetected for a long time. Regular preventive examinations by an ophthalmologist are therefore recommended. Treatment and prognosis depend on the location of the tumour, its size and type.

What are the different types of eye cancer?

The three most common types of eye cancer are

- Choroidal melanoma: is also called uveal melanoma and is one of the most common types of eye cancer in adults. Choroidal melanoma is caused by the uncontrolled proliferation of pigment cells in the choroid.

- retinoblastoma: almost exclusively affects children under the age of five and develops either in one eye (unilateral retinoblastoma) or in both eyes (bilateral retinoblastoma). A retinoblastoma grows very quickly and is caused by the uncontrolled division of retinal cells. The tumour first grows in the vitreous body of the eye and then spreads via the optic nerve to the brain. Although retinoblastoma is one of the most common forms of eye cancer in children in Germany, it only accounts for two per cent of all childhood cancers and is therefore a rather rare form of cancer.

- Eyelid tumour: can be either benign or malignant. A benign eyelid tumour can take the form of warts or fatty deposits, while a basal cell carcinoma is a malignant and aggressive type of eye cancer. Eyelid tumours are usually caused by UV radiation and on average often affect people with very fair skin.

What are the symptoms of eye cancer?

In many cases, eye cancer does not cause any symptoms for a long time. This is especially the case with retinoblastoma. It is only when the tumour gets bigger or affects other parts of the eye that symptoms such as reduced vision or blindness can occur. In the case of retinoblastoma, it often happens that the pupil lights up white when exposed to a certain light, like the flash of a camera (leukocoria). In common parlance, this is also called a "cat's eye", which can be an indication that a tumour is developing behind the lens.

Furthermore, squinting can be a sign that a tumour has developed in the centre of the retina. But also frequently occurring eye inflammations can indicate an increased intraocular pressure. In addition, a change in the colour of the iris as well as reduced vision can indicate eye cancer. It is advisable to have these signs checked by an ophthalmologist. The earlier eye cancer is diagnosed, the better the chances of a cure.

How is eye cancer diagnosed?

Eye cancer is diagnosed by an ophthalmoscopy. The eye is examined with an illuminated ophthalmoscope and can be supplemented with an ultrasound examination. For the diagnosis of pathological changes in the eye socket and in the skull, a magnetic resonance tomography (MRT) or a computer tomography can also be ordered. If it is determined that the eye cancer is already in an advanced stage, further examinations can also be ordered, such as an examination of the cerebrospinal fluid, the bones or bone marrow, and a chest X-ray.

If it is a retinoblastoma, which can be hereditary, the parents and siblings will also be examined. In this case, a genetic test can provide information about the hereditary risk.

How is eye cancer treated?

The type of treatment depends on the form of the eye cancer as well as its size and location. For the complete destruction of the tumour, the doctor has two treatment options:

- 1. the surgical removal of the tumour together with the eye (enucleation),

- 2. eyeball-preserving therapy, in which both the eye and thus the vision are preserved, but the malignant tumour growth is also stopped. This can be done, for example, with radiation and/or chemotherapy.

If the tumour is smaller and is located at the posterior pole and aud the peripheral retina, a so-called laser coagulation can be performed. This involves directing a laser beam onto the pupil, thereby destroying the tumour tissue. The treatment is done under anaesthesia.

Icing (cryocoagulation) of the tumour is also possible. During icing, the tumour is localised with a metal probe and frozen through. Since the tumour cells react sensitively to cold, they are destroyed during this procedure. However, icing has the disadvantage that a large part of the healthy retina is lost. In addition, the eyelids and the conjunctiva can swell temporarily.

If there is a medium-sized tumour, it can be treated with an applicator under general anaesthesia. The doctor first pushes the conjunctiva away and then sutures the applicator onto the sclera. After a certain dose of radiation, the applicator is then surgically removed. The duration of the treatment depends on the size of the tumour. The advantage of the treatment is that the tumour is targeted by the radiation, while healthy tissue is spared. However, it is possible that lens clouding may occur during the procedure, or that the retina or optic nerve may be damaged.

As an alternative to radiation therapy, so-called percutaneous radiation therapy can also be performed. In this case, the eye is held in position by vacuum contact lenses and irradiated. This type of treatment is usually limited to over five weeks and involves five sessions per week. If the treatment is used for particularly young children, it can also be carried out under anaesthesia.