What are sarcomas?

Sarcomas are rare malignant tumours that affect about 5,000 patients in Germany every year and thus account for almost one percent of all new cancer cases. They develop primarily (about 85 per cent of all sarcomas) in soft tissue such as muscle, fat and/or connective tissue. More rarely, they can also occur in the bones (about 15 per cent of all sarcomas). Sarcomas comprise about 100 different subtypes, the identification of which is extremely important for treatment.

What soft tissue tumours are sarcomas divided into?

In general, sarcomas are divided into the following three types of soft tissue tumours:

- benign and non-aggressive soft tissue tumours: such as a liposarcoma (belongs to the second most common soft tissue sarcoma after histiocytoma), a fibrosacroma (arises from connective tissue cells) or haemangiomas are localised tumours which do not grow into other tissue. Most often, these types of tumours occur on the arms or legs. In more rare cases, they can also affect the abdomen, pelvis, shoulders and/or head and neck.

- Intermediate soft tissue tumours: such as aggressive fibrosarcomas (desmoid tumours) grow directly into the neighbouring tissue. However, they usually do not metastasise to other parts of the body.

- Malignant soft tissue tumours (sarcomas): such as liposacomas or leiomyosarcomas (consisting of smooth muscle cells), which grow directly into the neighbouring tissue and can also spread metastases to distant organs.

Typically, soft tissue sarcomas spread tumour cells mainly through the bloodstream and often metastasise to the lungs, whereas metastases to the lymph nodes are much less common.

Angiosarcoma is a somewhat specialised subtype of soft tissue sarcoma. This is a malignant tumour that often occurs in the skin, liver, breast or spleen. Angiosarcoma originates from the lymphatic vessels (a lymphangiosarcoma) or the endothelial cells of the blood vessels (a haemangiosarcoma).

Into which bone tumours are sarcomas differentiated?

While bone tumours can be benign or malignant, bone sarcomas are always malignant. They originate in the cartilage tissue or directly in the bone, which distinguishes them from bone metastases. This is because the latter do not originate in the bones, but in other organs. The tumour cells have then metastasised to the bones.

The most common bone sarcomas include chondrosarcoma (a malignant bone tumour), osteosarcoma (the most common primary malignant bone tumour) and Ewing's sarcoma. Osteosarcoma and Ewing's sarcoma are particularly common in children, adolescents and/or young adults, while these two bone sarcomas are rare in adults over the age of 40. In turn, people over the age of 50 are more likely than average to develop chondrosarcoma.

A more specific subtype of bone sarcoma is rhabdomyosarcoma. This is a carcinoma that occurs mainly in childhood and develops from embryonic mesenchymal cells. These cells can still develop into skeletal muscle cells. A rhabdomyosarcoma can develop in any part of the body and can involve almost any type of muscle tissue.

What symptoms can sarcomas manifest themselves with?

Sarcomas usually do not cause any typical symptoms, which is why they are often diagnosed late. The first sign is a painless swelling or lump. If the swelling or lump expands, there may also be a feeling of tension in the affected area of the skin. Only when the sarcoma displaces nerves and/or grows into nerve tissue can pain occur.

If the sarcoma is superficial, it is usually discovered earlier than sarcomas that are deeper in the tissue or have settled in the chest or abdomen. If a bone sarcoma is present, it can lead to joint pain, stiffness of the joints or a bone fracture.

If a swelling is noticed that has not subsided after more than four weeks, a doctor should definitely be consulted to have the swelling medically clarified. This is especially true if the swelling is 5 cm in diameter, increases in size, causes (severe) pain and/or appears to be under the skin. If all these characteristics apply, the probability of a malignant tumour increases.

What are the causes of sarcomas?

The exact cause for the development of sarcomas is still unknown to medical experts. However, the following factors are considered to be possible risks for the development of a sarcoma:

- Rare genetic syndromes can favour the development of sarcomas.

- After radiotherapy, a sarcoma may develop at the site of the radiation.

- A certain type of human herpes virus can play a role in the development of Kaposi's sarcoma.

- The development of sarcomas in the liver is probably related to vinyl chloride.

- Environmental toxins and/or contact with certain chemicals can lead to sarcoma.

- Chronic inflammation can be a risk for soft tissue sarcoma.

What is the course of a sarcoma?

A sarcoma depends on various factors and therefore always progresses quite differently. In addition to the question of which subtype of sarcoma is present, it also depends on whether the tumour cells are malignant, what size the sarcoma has already reached, where the sarcoma is located and whether the sarcoma has already formed metastases. All these factors determine whether the sarcoma can be surgically removed.

How is a sarcoma diagnosed?

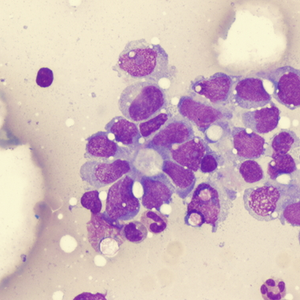

Because sarcomas are rare and can take many different forms, diagnosis is not always easy. However, identifying the sarcoma subtype is a prerequisite for optimal treatment. To make the diagnosis, doctors will first take the patient's medical history and then perform a thorough physical examination. Using imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or computed tomography (CT), the doctor can determine how far the tumour has spread. By taking a tissue sample (biopsy) and examining it for fine tissue, a definite diagnosis of the sarcoma can be made.

How is a sarcoma treated?

Patients who have a well-founded suspicion of a sarcoma or whose diagnosis has already been confirmed should go to a centre that specialises in the treatment of sarcomas. In this special sarcoma centre, experts from different fields work hand in hand. In order to initiate the appropriate therapy measures, the exact type of sarcoma must first be determined. To do this, the doctors must know whether the tumour is growing locally, has already grown into neighbouring tissue and whether it has spread to metastases. But the patient's general state of health and age also play an important role in the choice of treatment.

Treatment methods for soft tissue sarcomas

Soft tissue sarcomas can in principle be treated by surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy. However, soft tissue sarcomas can also be treated with drugs.

If it is a localised soft tissue sarcoma, it can be removed as completely as possible by surgery. If this is successful, the chances of recovery are very good. In some patients, it may also be necessary to order radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy before the operation (neoadjuvant treatment). If additional treatment is necessary after the operation, for example in the form of post-operative radiation, doctors refer to this as adjuvant therapy. This is to reduce the risk of the tumour forming again. In some cases, both pre- and post-treatment may be ordered.

Treatment methods for bone sarcomas

Bone sarcomas are also treated mainly by surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy. Similarly, targeted drugs can promise a cure when treating individual bone sarcomas. Similar to soft tissue sarcoma, the type of sarcoma, the location of the tumour and its size are also important for bone sarcoma. But also the question of whether the tumour has already grown into the neighbouring tissue and has already formed tumours plays a role in the treatment method. In addition, there is the patient's general state of health and age.